The minerals in our phones that could help with climate change

How will the world stop its addiction to the oil that is causing climate change?

The answer is in your pocket.

Critical minerals - used in our phones - are needed to make clean energy like wind and solar power batteries to heat our homes and help transport us.

Scroll down to take a look inside your phone and see which minerals it’s powered by.

A mobile phone expanded to show its component parts including a screen, micro chips, cables and a battery.

If you stripped the mobile apart, this is what you’d see.

Here are the minerals it’s powered by. The battery contains nickel, lithium and cobalt.

These minerals are crucial to power our electric vehicles, homes and offices and to reach net-zero emissions targets for 2030.

The phone connecting cable, circuitboard, battery and casing are highlighted.

Nickel is found in other parts of the phone as well. It’s also in many products, including medical equipment.

The phone battery is highlighted.

Lithium is a mineral that’s also prescribed as a ‘mood stabiliser’ drug to treat mental health issues.

The phone battery is highlighted.

Cobalt is mainly used in rechargable batteries. It’s also found in jewellery.

Why are we focused on batteries? Because these three minerals are crucial for countries to combat climate change.

Batteries in electric vehicles make up a large part of the demand for critical minerals.

In 2020, one in 25 new vehicles sold worldwide were electric, says the International Energy Agency (IEA). This year, it’s set to be one in five.

Electric vehicles are four or more times as clean as engines that burn fossil fuels, if they are charged from a green source, says the IEA.

Green technologies like, solar panels, electric vehicles and wind turbines will all need critical minerals.

There will be a huge growth in electric vehicles and grid storage over the next 20 years, so we will need a lot of these minerals.

Let’s have a look at the demand for critical minerals.

How will demand change as we aim for net zero? (Net zero means no longer adding to the total amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.)

This mine represents the amount of minerals which we need (not drawn to scale).

This is how much nickel was used worldwide last year: 3,200 kilotonnes (KT) (that’s the weight of 3.2 million cars).

To achieve net zero by 2030, we need an estimated 5,700 kilotonnes of nickel.

But the current estimated supply for nickel is only 4,140 kilotonnes - well short of the estimated net-zero demand by 2030.

Let’s have a look at lithium and cobalt.

Lithium: Demand in 2022, 146 Kt; Net zero emissions by 2030, 702 Kt; Expected supply by 2030, 420 Kt.

By 2030, we must increase lithium supplies if we are to limit global warming to 1.5C.

Cobalt: Demand in 2022, 200 Kt; Net zero emissions by 2030, 346 Kt; Expected supply by 2030, 314 Kt.

By 2030, we need to increase the supply of cobalt in order to limit global warming to 1.5C.

Let’s see where these minerals are mined around the world.

In 2022, Indonesia, the Philippines and Russia produced two-thirds of the world’s mined nickel supplies.

Australia, Chile and China mined 91% of the world’s lithium supplies.

The Democratic Republic of Congo (DR Congo), Australia and Indonesia mined 82% of the world’s cobalt supplies.

D R Congo, cobalt: 74%; Indonesia, nickel 49%; Australia, lithium 47%

Mining of critical minerals is highly concentrated in a handful of countries. Here are the top producing countries for each mineral.

Where are these minerals processed?

Processing is even more geographically concentrated than mining.

China, cobalt 74%, lithium 65%; Indonesia, nickel 43%.

China processes a large share of lithium and cobalt, while Indonesia processes the most nickel.

China, cobalt 74%, lithium 65%, nickel 17%.

China also processes 90% of rare earth elements, which are used in modern technologies.

"History has shown us that failing to properly diversify supplies and trade routes of essential resources comes with profound risks."

"History has shown us that failing to properly diversify supplies and trade routes of essential resources comes with profound risks."

Tim Gould, IEA

A mining machine moves a salt by-product at a lithium mine in Chile

Lithium mine in Chile

What are the obstacles to supplying all these critical minerals?

A typical mine can take 15 or more years to establish and we’re less than seven years away from 2030.

A woman works at a cobalt mine in DR Congo, under very poor conditions

Cobalt mine in DR Congo

Once a new reserve is found, you may not have the infrastructure - like roads - in place to exploit it.

New mines may be unsafe and there needs to be engagement with local communities to ensure fair and equitable extraction.

The expansion of industrial-scale cobalt and copper mines in the Democratic Republic of the Congo has led to the forced eviction of entire communities and grievous human rights abuses.

The expansion of industrial-scale cobalt and copper mines in the Democratic Republic of the Congo has led to the forced eviction of entire communities and grievous human rights abuses.

Amnesty International

As time goes by, batteries will need to be recycled.

Scientists believe most electric vehicle batteries must be changed within 20 years.

Researchers at the UK’s University of Birmingham say less than half of battery materials can be recycled at present.

But they say that 80% could be within the next two decades.

We need to rethink the way we build batteries to make it easier to recycle them.

We need to rethink the way we build batteries to make it easier to recycle them.

Prof Paul Anderson of the University of Birmingham, UK

With the amount of batteries we're producing, you can't recycle your way out of that. There aren't enough minerals being dug up now to make all of the batteries we’re hoping to make.

With the amount of batteries we're producing, you can't recycle your way out of that. There aren't enough minerals being dug up now to make all of the batteries we’re hoping to make.

Prof Paul Anderson of the University of Birmingham, UK

Comedy Wildlife Photography Awards

Comedy Wildlife Photography Awards

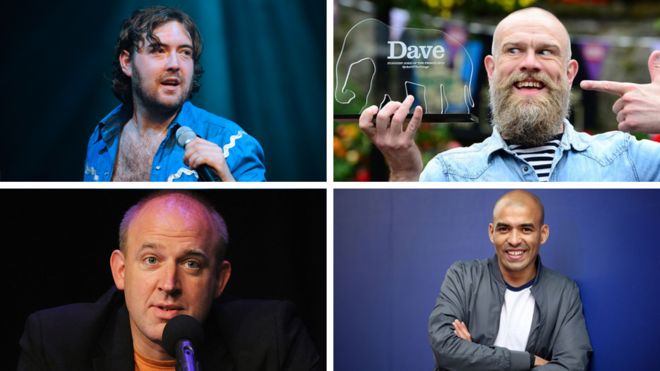

Ten years of the Fringe's funniest jokes

Ten years of the Fringe's funniest jokes

David Attenborough gets the trance treatment

David Attenborough gets the trance treatment