It affects millions of people, but few of us know we have it.

I certainly didn’t.

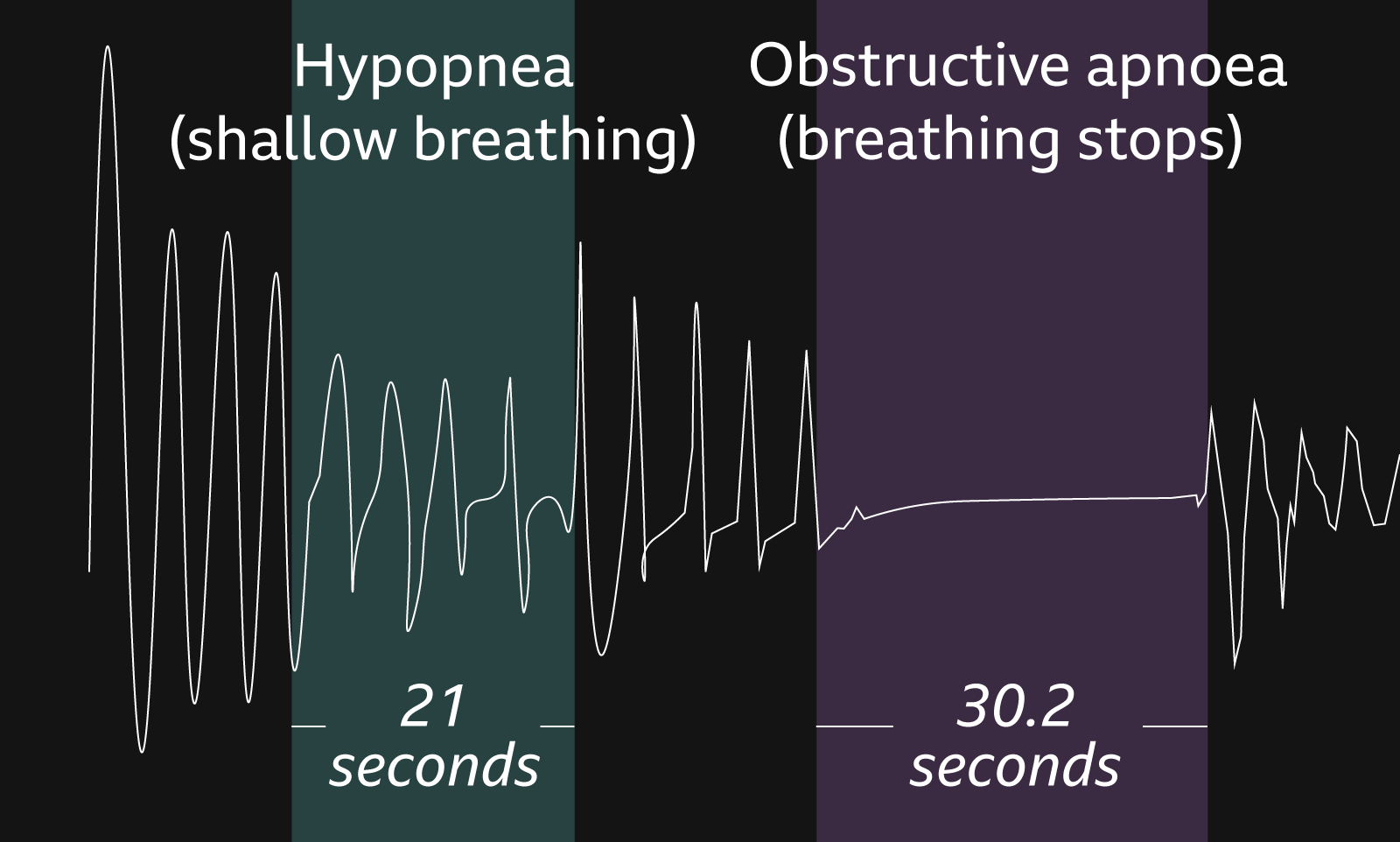

Sleep apnoea is a serious disorder where your breathing stops and starts while you sleep. In the most severe cases, people can stop breathing every minute for more than 10 seconds at a time.

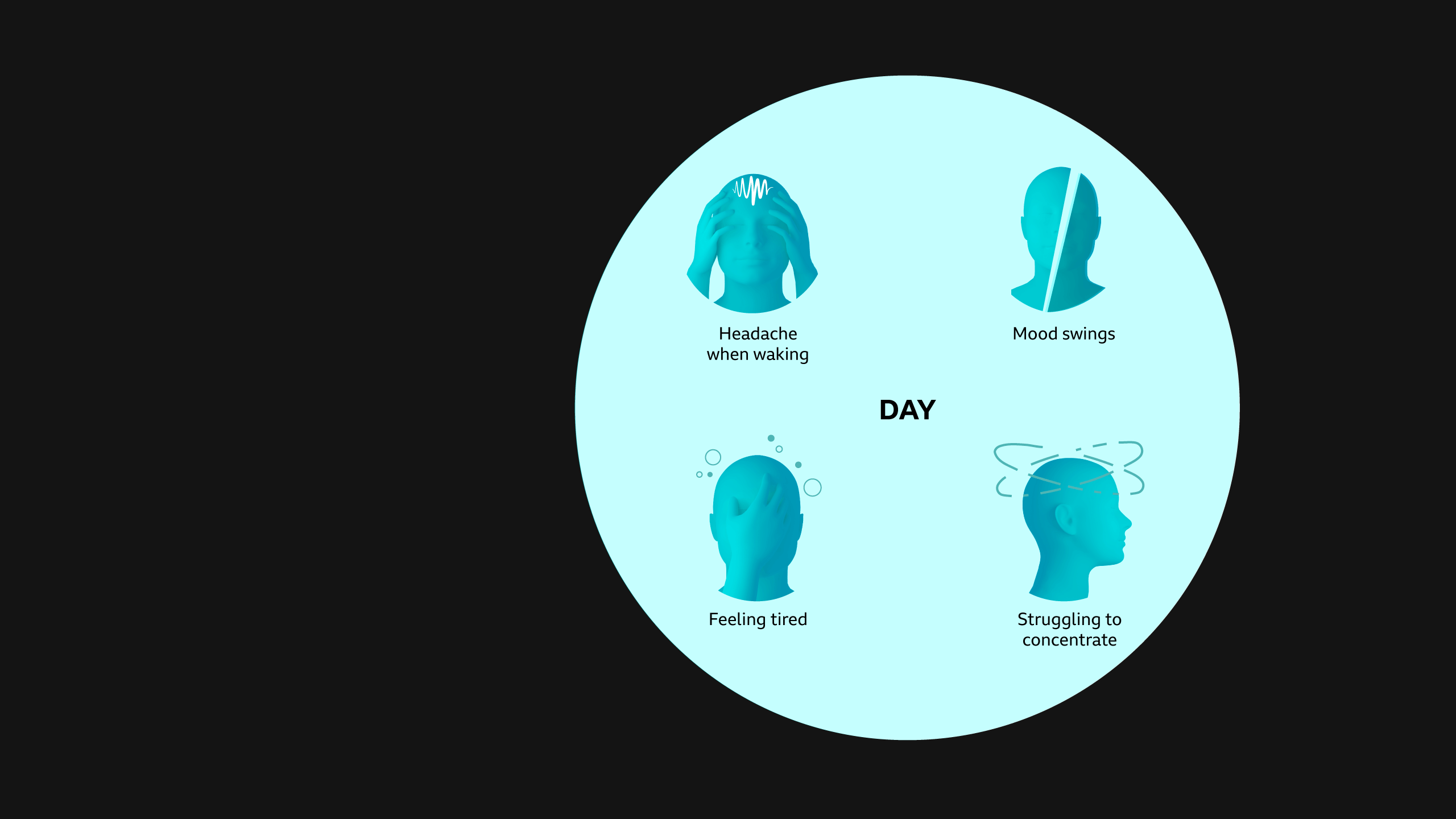

They often wake up with no idea what has happened but find they are inexplicably exhausted during the day.

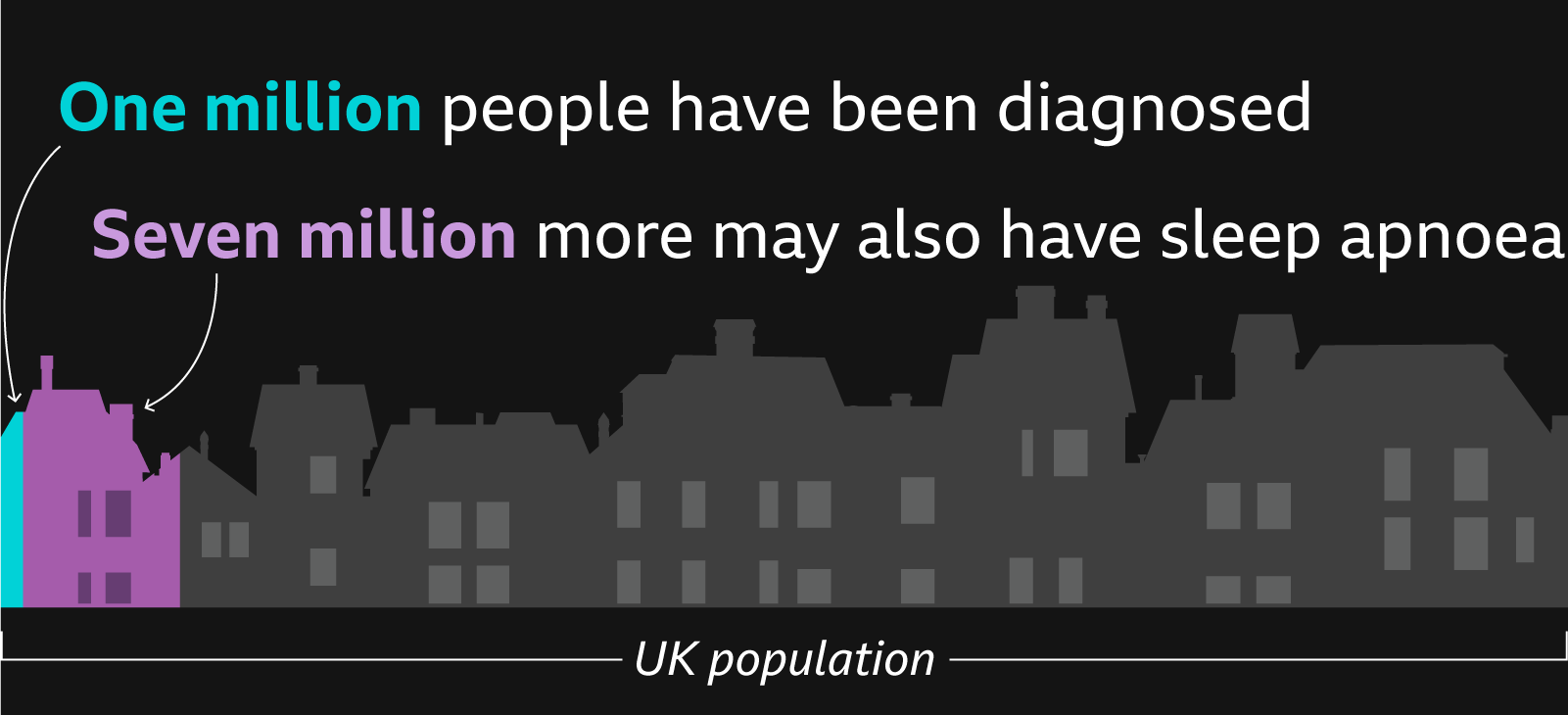

According to a recent report in the Lancet, current figures suggest about eight million people in the UK may have it but only a fraction of those have been diagnosed.

That number is going up, especially among younger people, partly because of rising rates of obesity, which increases your risk. Undiagnosed and untreated sleep apnoea can reduce your life expectancy by a decade and lead to type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure and heart disease.

"We need to raise awareness of this condition," Dr Prina Ruparelia, a respiratory consultant at Barts Health NHS Trust in London, says. “So how about you have a sleep study and we see what happens?”

I agree and get myself set up. A nasal cannula monitors my airflow, while chest and abdominal belts calculate the amount of effort I am putting into breathing. A small finger clip measures my heart and oxygen rates.

Around the country people are waiting months - and in some cases for as much as a year - to take part in sleep studies like this, so in an effort to reduce long waiting times, patients are often able to take these test kits home. Each one costs thousands of pounds.

A common misconception is that sleep apnoea only affects older, overweight men. They are at greater risk but it can impact people of all ages, genders, and body types, including slim women in their 40s - people like me.

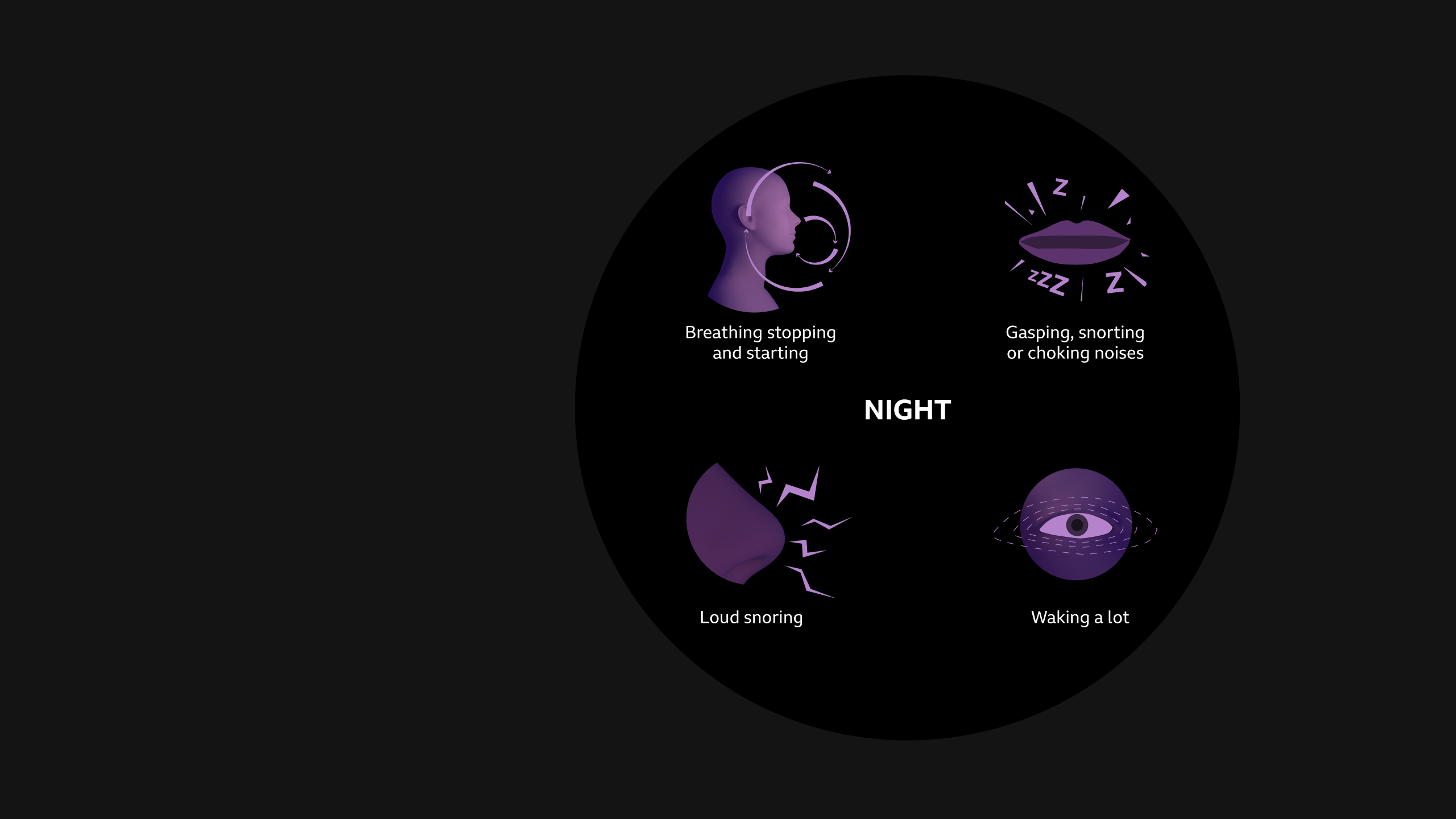

As a vocal sleeper (others might say loud snorer) and someone who enjoys an afternoon nap, I meet two of the three main diagnostic criteria for sleep apnoea. And after speaking to people who have had the joy of sleeping next to me - I discover I also meet the third, which is gasping for air while I sleep.

As I settle down in my bed, the sensors and infrared camera pointing at me as I try to fall asleep make feel like an animal being filmed for a David Attenborough documentary.

But this test will show if I have sleep apnoea and, if I do, give an indication of which type.

“Good morning,” Ruparelia says when I drop the kit off the next morning.

She’s so eager to raise awareness of sleep apnoea she is going to analyse my results outside her normal working hours - and it’s important to note I’m not skipping any queues.

“How did you sleep?”

“Like a log,” I reply.

“Not quite,” she says, as she shows me her analysis of the data that’s been collected while I was sleeping.

The sensors have picked up episodes of sleep apnoea. Graphs show instances where the amount of air flowing into my body falls by more than 90% - a clear indication that I had stopped breathing.

“You can see that your oxygen levels have dropped, and your heart rate has increased,” Ruparelia says, pointing at the screen.

In the space of an hour, I had stopped breathing 10 times, each lasting about 30 seconds.

“But don’t worry,” she says.

Don’t worry? I almost say out loud.

“Your body does wake itself up,” Ruparelia continues, “you do breathe in the end.”

She explains that I only stop breathing when I sleep on my back - due to a slightly narrow airway and my muscles relaxing more than they should.

But I have no recollection of any of this.

“Often people don’t realise and it’s their partners who might notice,” Ruparelia explains. “The snoring and the gasping for air are red flags.”

I see myself as a fit, wannabe triathlete, not someone who stops breathing in the middle of the night, so being diagnosed with a mild case of obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) comes as a shock.

What are the symptoms of sleep apnoea?

In severe cases, the effects on the body can be huge. Depending on where you live, accessing treatment can be difficult due to long waiting lists.

It took nearly a year for Zoe Dodds to receive her Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP) machine, a device which pumps air into a mask she wears over her mouth every night while she sleeps.

The 27-year-old from Birmingham was diagnosed with severe sleep apnoea in January 2024 and discovered she had been stopping breathing every two minutes while asleep.

“Life was exhausting, but I didn’t think this would be the reason I was so tired,” says Zoe - who says she cried when she received the letter with her diagnosis. “I honestly thought that overweight, older men got it - not me.”

The CPAP machine ensures Zoe can sleep better, and she now has more energy for her children and her job. She has started exercising and lost five stone (32kg).

Zoe has recently taken part in another sleep study and the number of times she stops breathing while asleep has plummeted - from 31 to just four an hour, within the normal range.

She no longer needs the CPAP machine. “Getting that diagnosis saved my life,” she says.

While these devices are seen as the gold standard treatment by the NHS, they do not work for all patients. Numerous studies into adherence rates suggest as few as 40% of those prescribed with a CPAP who continue to need it are still using it after a year.

Some people struggle to sleep wearing such a large mask all night. Others find it claustrophobic. For some it’s down to the cost of running the machine on a nightly basis.

Some sleep experts think another treatment - not currently widely available on the NHS - could be a gamechanger for people like me, with mild to moderate sleep apnoea.

It’s a mouthguard, known as a mandibular advancement device (MAD), that patients can clip in and wear while they sleep, which gently pulls the lower jaw forward, helping to keep the airway open overnight.

Prof Ama Johal, a consultant orthodontist with a special interest in dental sleep medicine at St Bart’s NHS Trust, trains other dentists how to fit these devices, but says thousands of patients are missing out because they aren’t more widely available.

"So many patients are left with nothing,” Johal says, "We need a device like this to be widespread and easily accessed through the NHS."

While a GP or respiratory consultant can prescribe a MAD and will oversee and manage a patient’s care, only specially trained dentists are able to fit them.

As the clinical lead for 32co, a private company which specialises in these devices, he does have a vested interest but, after 30 years of clinical and research experience in the NHS, he has seen how important this alternative treatment is for patients. Many studies agree that they are effective, and can have a higher tolerance rate for patients than CPAP machines.

To date, about 2,000 dentists across the UK have been trained on how to fit a MAD, albeit privately at a cost of about £700 to £1,000.

At a dental clinic in Walkden, Greater Manchester, I’m having scans taken of my mouth and I am about to get fitted with a MAD.

“Ouch,” I whimper as the dentist, Simon Betts, fits my device. I can already feel it drawing my jaw forward.

Looking more like a Bond villain than a woman who is about to get a good night’s sleep, I am keen to find out if it can improve my sleep.

A couple of weeks on I do have a bit more energy. My desire for an afternoon nap is no longer daily and my snoring has reduced - my husband has stopped moaning about it as much, anyway.

I’ll keep wearing it, for now.

And if you’re reading this and think you might have sleep apnoea, talk to your GP. If your symptoms are mild they may suggest lifestyle changes that may help - these can include losing weight, regular exercise and sleeping on your side.

Other changes that can help are drinking less alcohol before going to sleep and stopping smoking.

For those with more serious symptoms your doctor might suggest taking part in a sleep study like I did.